When silver collapsed 40% in January, retail investors lost billions while major banks profited. The reason lies in how modern markets are built, not necessarily how they’re manipulated.

When silver crashed 40% in three days this January, wiping out $150 billion in value, the story you heard was simple. The Federal Reserve nominated a tough new chairman, and scared investors sold their gold and silver. Case closed.

Except the crash started three hours before that announcement.

What really happened reveals something far more troubling about how modern markets work and why regular investors keep losing to Wall Street’s biggest players.

The Setup: Different Players, Different Rules

Think of it like this: Imagine you’re playing poker at a table where some players are professional dealers who work at the casino. They’re not cheating; they’re just playing by a different set of rules. They know when the casino plans to raise table minimums. They have access to a line of credit from the house. They can see the odds differently because they understand the game’s mechanics from the inside.

That’s essentially the position of institutional traders versus retail investors in the silver market.

In early January, everything looked perfect for silver. The metal had jumped 132% in 2025. Supply was tight (five straight years of shortages). Big central banks were buying. AI data centers needed it. Solar panels needed it. Even nuclear power plants needed it.

Regular investors piled in. They put a record $1 billion into silver funds in January alone. On January 26, trading in the silver ETF called SLV (NYSE:SLV) nearly matched the entire S&P 500’s main fund: something that would have seemed impossible a year earlier.

Reddit forums buzzed with excitement. Twenty times the normal chatter about silver, according to JPMorgan’s own tracking. People thought they’d found the trade of a lifetime.

They had. Just not for themselves.

The Structural Advantages: Four Ways Institutions Could Profit

Here’s what makes this story worth examining. One bank (JPMorgan) was positioned to profit in four different ways on the exact same day the market crashed. This wasn’t illegal. It was structural advantage built into how markets operate.

Move One: Access to Emergency Liquidity

On December 31, just before the crash, banks borrowed a record $74.6 billion from the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending window. The previous record was $50 billion; this was 50% higher.

This facility (called the Standing Repo Facility) exists specifically to provide short-term liquidity to eligible financial institutions. It’s designed to prevent funding crises. But here’s the structural reality: only certain institutions qualify for access.

Why does this matter for the crash? Because at the exact same time, the exchange where silver trades was raising margin requirements by 50% in one week. Large institutions with derivatives positions would need substantial cash immediately.

The Federal Reserve’s emergency facility provided that cash at favorable rates to eligible institutions. Retail investors had no equivalent access to emergency central bank funding.

This isn’t about favoritism. It’s about how the financial system is architecturally designed: central banks lend to banks, not to individuals.

Move Two: The Margin Mechanics

This is how margin requirements work in plain English: When you bet on silver going up using borrowed money, the exchange makes you put up cash as insurance. If silver falls, they demand more cash. If you can’t pay, they automatically sell your position.

On December 26 and December 30, the CME exchange raised these requirements by 50% total. Suddenly, a trader who had put up $22,000 needed $32,500 (an extra $10,500 in cash, immediately).

Most retail traders don’t have $10,500 readily available in their trading accounts. So their brokers sold their silver positions automatically at whatever price the market offered during the selling cascade.

Meanwhile, institutions with access to the Federal Reserve’s facilities had more options. They could draw on credit lines, access emergency lending, or quickly move capital between accounts. This didn’t prevent all liquidations, but it gave them more time and flexibility.

And so, retail positions were sold during the panic, often at the worst prices. Institutional positions could be managed more strategically.

Move Three: The Authorized Participant Privilege

This is where market structure gets technical, but it’s worth understanding because it explains a major institutional advantage.

The bank serves two roles in the silver market: they store all the physical silver for the biggest silver fund (SLV), and they’re also an “authorized participant,” which means they can create or destroy shares of that fund in large blocks.

On January 30, when panic hit, SLV shares started trading at an unusual discount. The fund’s shares cost $64.50, but the silver they represented was worth $79.53. That’s a 19% gap (extraordinary in normal markets).

Authorized participants (a small group of large financial institutions) can exploit this gap. They buy shares at $64.50, exchange them for physical silver worth $79.53, and capture the $15 difference. On January 30, about 51 million shares were created, representing roughly $765 million in potential arbitrage profit.

This isn’t illegal or even unethical; it’s exactly what authorized participants are supposed to do. Their arbitrage helps keep ETF prices aligned with their underlying assets. But it’s a privilege available only to institutions with the capital, infrastructure, and regulatory approvals to act as authorized participants.

Regular investors can’t access this mechanism. They could see the discount, but they couldn’t exploit it.

Move Four: Strategic Positioning in Derivatives

JPMorgan also held a substantial short position in silver, meaning they’d bet on silver going down, or were hedging other positions. As silver rose to $121 in late January, those positions were underwater.

On January 30, at the bottom of the crash ($78.29), they took delivery of 3.1 million ounces. CME records show they accepted 633 contracts at that price.

The timing is noteworthy. In a single day:

- Margin requirements had forced widespread liquidation

- Emergency Fed lending provided liquidity to large institutions

- ETF discounts created arbitrage opportunities

- And derivative positions could be closed at favorable prices

Did they plan this sequence? That’s impossible to prove. But they were structurally positioned to benefit from it in multiple ways simultaneously: something only possible for institutions with their unique combination of roles and access.

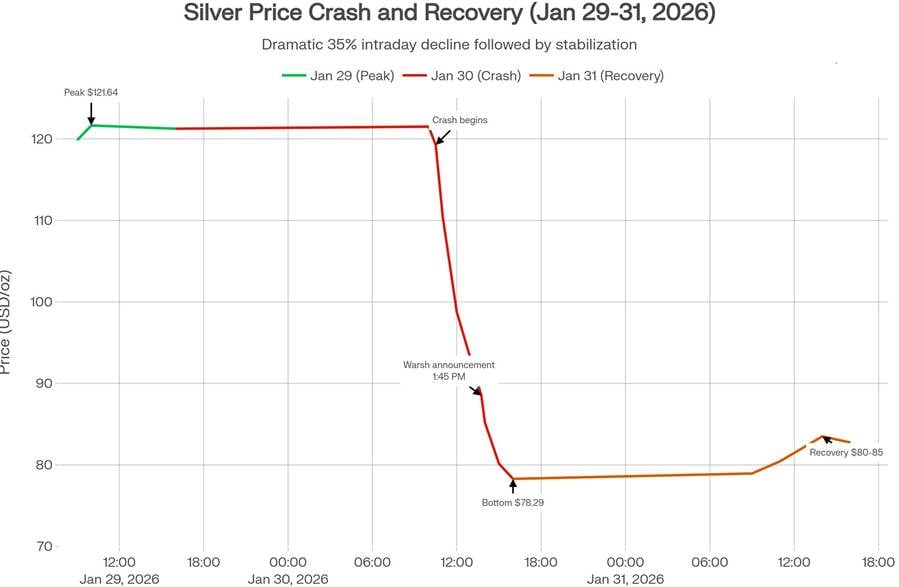

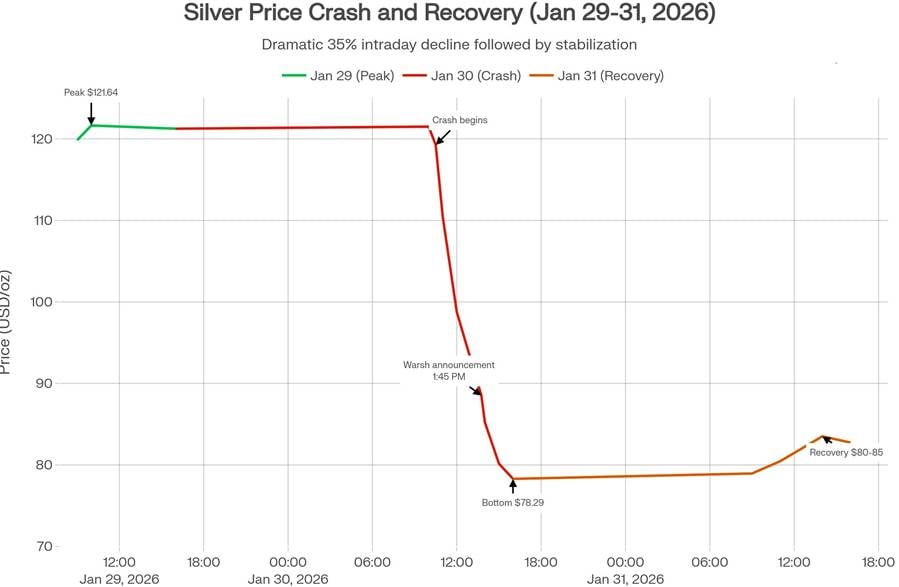

The chart above shows intraday silver prices for January 29-31. Silver peaked at $121.64 on January 29. On January 30, the crash began accelerating around 10:30 AM, dropping to $119.25. By 1:45 PM (when Kevin Warsh’s Federal Reserve nomination was announced) silver had already fallen to $88.50, a 27% decline from the peak. The three hours between crash start and announcement suggests the market dislocations preceded the news event, not the reverse.

The Timing Question: What Really Triggered the Crash?

Now let’s examine the official narrative about what caused the crash.

Kevin Warsh was nominated as Federal Reserve Chair at 1:45 PM Eastern time on January 30. Most news coverage attributed the precious metals crash to this announcement. The theory being that markets feared a more hawkish Fed chairman would keep interest rates higher, reducing the appeal of non-yielding assets like gold and silver.

But there’s a timing problem: silver started falling sharply at 10:30 AM (more than three hours earlier).

Does this mean the Warsh narrative is wrong? Not necessarily. Markets often move on rumors or expectations before official announcements. Traders may have positioned ahead of expected news.

But it does raise questions. If the crash was fundamentally about Fed policy expectations, why did it accelerate hours before the announcement? And why was the selling concentrated in precious metals rather than across all interest-rate-sensitive assets?

The news connecting the Fed news to market moves were explaining price action through available news. When major news breaks on the same day as dramatic price moves, that becomes the accepted explanation.

The alternative explanation is more mechanical though: margin increases forced liquidations, creating a cascade that fed on itself. The Warsh announcement may have accelerated an already-in-progress crash, but it didn’t start it.

Understanding the Structural Divide

You might think: “Markets always have winners and losers. What’s different here?”

What’s different is the degree of structural advantage built into the system.

When retail investors trade silver:

- Margin calls trigger automatic liquidation within minutes

- No access to Federal Reserve emergency lending facilities

- No ability to create or redeem ETF shares

- No advance notification of exchange rule changes beyond public announcements

- Limited ability to trade during market stress

When major institutions trade silver:

- Access to credit lines and Fed facilities provides liquidity buffer

- Authorized participant status enables ETF arbitrage

- Clearing member status means earlier awareness of exchange decisions

- Infrastructure to continue trading when markets are stressed

- Capital reserves to add to positions during panics

This isn’t about institutions being smarter or more disciplined. It’s about access to tools and information that retail investors structurally cannot obtain (regardless of wealth, experience, or sophistication).

The Questions This Raises About Market Structure

This article reveals several structural features of modern markets worth examining:

Layered advantages compound. When an institution has authorized participant status AND clearing member status AND Federal Reserve access AND custody of physical assets, these advantages can align during market stress in ways that systematically favor that institution.

Information flows at different speeds. Exchange rule changes reach different market participants at different times. Clearing members and authorized participants often learn of structural changes before retail investors, creating a timing advantage.

Emergency facilities create selective support. When central banks provide emergency liquidity to “eligible institutions” during market stress, it stabilizes only part of the market. This can inadvertently amplify the disadvantage faced by participants without such access.

No explicit coordination required. The structure itself creates incentive alignment. Institutions don’t need to coordinate when the rules naturally advantage them during volatility.

Understanding these features doesn’t require believing in manipulation or conspiracy. It just requires recognizing that markets are designed systems, and those designs have built-in advantages for certain participants.

What This Means for Retail Traders

If you trade precious metals (or any leveraged instruments), several lessons emerge from this episode:

Understand access differences. You’re not competing just with other retail traders. Some participants have structural advantages in information, liquidity access, and trading mechanisms. These aren’t necessarily unfair, but they’re real.

Recognize leverage risks. Margin trading and leveraged products can force you to sell at the worst possible moment. Institutions with deeper capital bases and credit access have more flexibility during market stress.

Consider market structure. ETF discounts, margin requirements, and exchange rules affect different participants differently. Understanding these mechanics helps you assess when structural forces might work against your position.

Watch timing patterns. When margin requirements increase sharply, especially in multiple steps, it often precedes volatility. This isn’t secret information (exchanges announce these changes), but recognizing the pattern matters.

None of this means don’t trade. It means understanding what kind of market you’re participating in. The silver crash of January 2026 wasn’t random bad luck. It was mechanically predictable once you knew about margin increases, institution positioning, and structural advantages.

Some participants knew these factors. Others didn’t. That lack of information is worth considering.

This analysis is based on publicly available data including CFTC reports, CME delivery records, Federal Reserve H.4.1 balance sheet releases, and ETF creation/redemption disclosures.

Benzinga Disclaimer: This article is from an unpaid external contributor. It does not represent Benzinga’s reporting and has not been edited for content or accuracy.

Recent Comments